Study investigates child abuse incidence during the pandemic

- Published June 29, 2022

When the world shut down due to COVID-19, families lost access to resources and children had fewer interactions with adults outside their homes. As normal routines disappeared, the stress and isolation seemed like a set up for increased child abuse. But on the other hand, families were together, potentially with more caregivers reliably around, and some may not have had the same day-to-day pressures. In addition, many families received governmental help. Could this have reduced physical abuse?

To complicate matters, initial publications on the topic showed mixed results. Specifically, several reports from individual institutions found increases in sentinel injuries (apparently minor injuries that could represent further abuse), sexual abuse, and neglect. Conversely, multicenter studies showed decreases and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported a sharp decline in abuse followed by rate normalization.

So did physical abuse actually increase or decrease during the pandemic? To answer this, Barbara Chaiyachati, MD, PhD, and colleagues at the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) looked at over 1.5 million ED encounters at nine children's hospitals between January 1, 2018 - March 31, 2021, using the PECARN registry. They found approximately 10,000 visits for possible abuse. They also used several methods to describe the severity of encounters such as injury severity and hospital disposition.

Because it is difficult to identify encounters for abuse in hospital records, they used three methods:

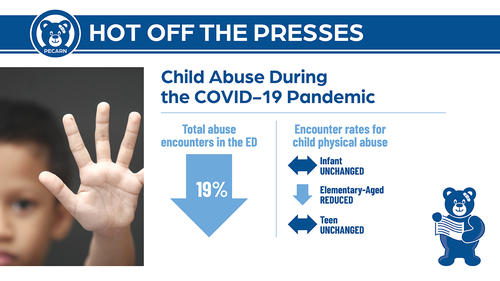

- Abuse diagnosis codes: One way is to identify a billing code (ICD-10) for abuse. The encounter rate for abuse per day decreased by 19% from 4.6 pre-pandemic to 3.8 during the pandemic. This decrease was seen in school aged children 2-13 years old, but young children <2 years old and older children >13 had the same encounter rate. Also, this reduction was predominantly in low severity (minor) abuse, not in severe abuse.

- High-risk injury codes: Sometimes clinicians don’t make the diagnosis of abuse with the specific ICD-10 code for abuse in the ED setting but will diagnose injuries that are very concerning for abuse such as rib fractures or intracranial hemorrhage in young children without other explanations. They found ED encounters for these concerning injuries decreased by 10% during the pandemic across all demographics. Again, this reduction was predominantly in low severity (minor) abuse not in severe abuse.

- Skeletal survey: Skeletal surveys (multiple X-rays of the body of young children to look for hidden fractures) are often used in the ED to screen for abuse and are not often used for any other diagnosis in the ED. While there was no reduction in total collection of skeletal survey numbers, there was a reduction in low severity encounters identified by this method – with no change in high severity.

The results: Lower severity physical abuse encounters decreased across all three sets of analysis while more severe physical abuse encounters did not change. Encounters for skeletal surveys did not decrease so clinicians were still able to screen for abuse but saw less severe abuse less frequently.

What does this mean? It is possible abuse did truly occur less often because there were novel protective factors during the pandemic, such as more caregivers at home, financial resources for families in need, or other factors. Or maybe abuse occurred as frequently or even more often—but it was not identified and reported. School personnel are typically the most common reporting source, and it is easy to imagine that interactions may have been different, particularly during periods of virtual schooling.

“The more severe child physical abuse that required emergency attention related to severe injuries did not change because people had to seek attention for those injuries – but we know that harm does not always mean injuries that require emergency care,” says Julia Magaña, MD, co-chair of the PECARN Dissemination Working Group. “Further studies are needed to sort out what this all means, but for now we know less severe abuse identified in the ED occurred less frequently, but more severe physical abuse did not change during the pandemic.”

“These results demonstrate important nuances in our efforts to understand occurrence of child abuse during the pandemic,” adds Chaiyachati. “Our hope is that this research leads to further investigation, and, as a result, may help inform appropriate interventions for at-risk children.”

Read the full article, “Emergency Department Child Abuse Evaluations During COVID-19: A Multicenter Study,” in the June 16 Pediatrics.